C Source Code to x86 Binary

This blog post details how C source code is compiled into x86 binary.

Post Outline

Source Code to Executable

How is a program (specifically in C) that someone writes understood and executed by the computer? This is a multistep process that turns the source code, written by the programmer, into machine code, which can be executed by the machine. We will follow the process with the example C code below.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int x = 1 + 2;

printf("Hello world!\n");

return 0;

}

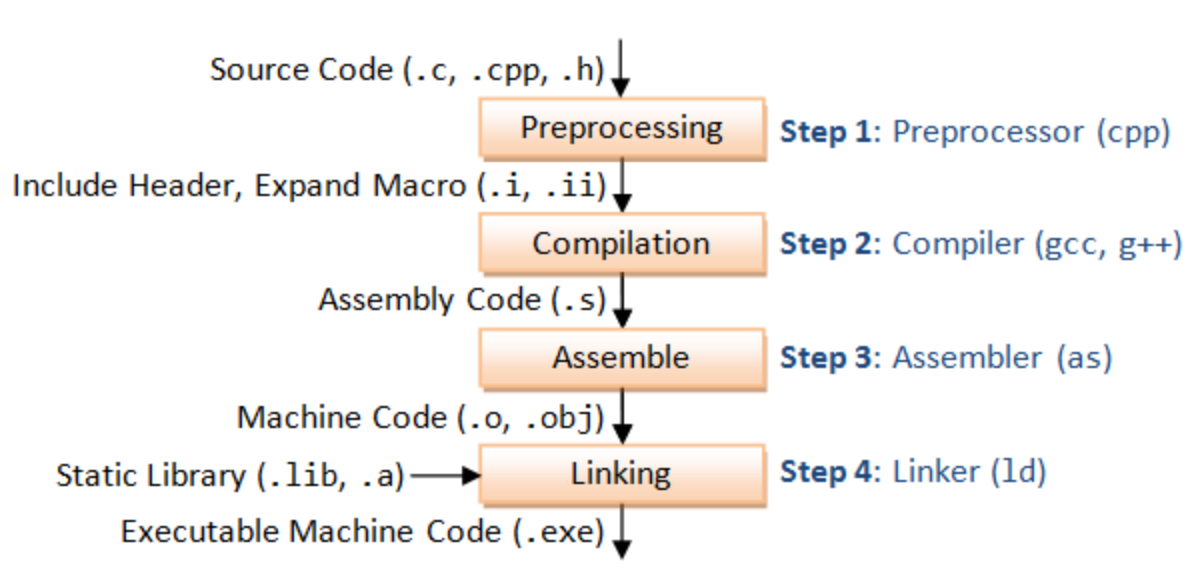

Here is an image detailing the whole process.

Preprocessor and Compiler

First, the source code is put through a preprocessor. In the case of the C code, this could be including header files and expanding macros. Then, a compiler parses the source code and turns it into an Abstract Syntax Tree, an internal representation of the program. The compiler then puts the code through many different intermediate representations that each optimize the code (e.g. removing unused code, loop unrolling). The result of the compiler is assembly code, which is still human readable.

Calling Conventions Aside

Below is the assembly representation of the above example C code.

0000000000001135 <main>:

1135: 55 push %rbp

1136: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

1139: 48 83 ec 10 sub $0x10,%rsp

113d: c7 45 fc 03 00 00 00 movl $0x3,-0x4(%rbp)

1144: 48 8d 3d b9 0e 00 00 lea 0xeb9(%rip),%rdi # 2004 <_IO_stdin_used+0x4>

114b: e8 e0 fe ff ff callq 1030 <puts@plt>

1150: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

1155: c9 leaveq

1156: c3 retq

1157: 66 0f 1f 84 00 00 00 nopw 0x0(%rax,%rax,1)

115e: 00 00

We can see the C language calling conventions in the snippet.

There is a __libc_start_main() function that initializes the execution environment and calls the main() function with the appropriate arguments.

We can see the standard subroutine prologue, body, and epilogue in the assembly code.

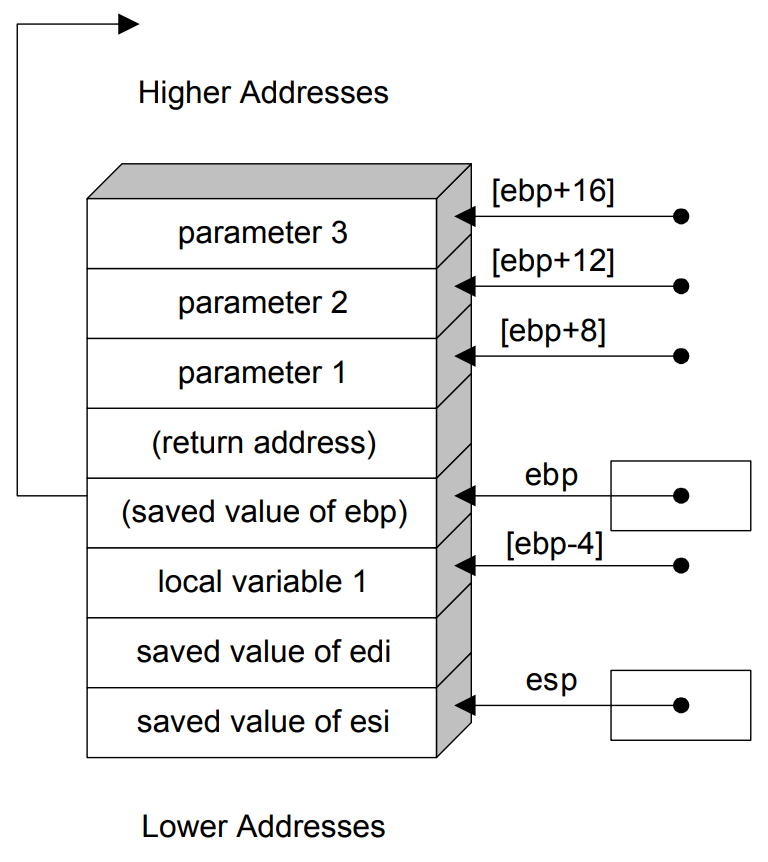

Below is an image of the stack in memory during the execution of some function with three input parameters and a local variable.

Note that the architecture below is 32 bit so the registers start with e as opposed to r.

Subroutine Prologue

First, we push the old base pointer value stored in %rbp, the register for the base pointer, onto the stack.

Then we move the value that the stack pointer %rsp is pointing to into %rbp’s address.

There is then a sub $0x10,%rsp, which moves our stack pointer down the stack with some space between the saved value of the %rbp base pointer.

This middle space will contain local variables that will be filled in the subroutine body.

Subroutine Body

We see that the value 0x3 is moved into -0x4(%rbp), the location of the local variable x.

We also see that there is a puts() call where we might have expected a printf() call.

This is because the compiler saw that we were not passing in any parameters to printf() and called puts() instead, which only takes a single argument.

We also see that the value 0x0 is moved into the register %eax.

The register %eax stores the return value, which in this case is 0 as can be seen in the source code.

Subroutine Epilogue

We see there a leaveq instruction.

At this point in the function, we have finished our work in the current function being called (i.e. the callee) and want to return to the previous function (i.e. the caller).

Therefore, we want to deallocate our local variables and restore our base pointer, which marks the start of a function’s stack frame to its previous value.

Both of the above actions are done with the leaveq instruction, which copies the frame pointer in the %rbp register into the stack pointer %rsp.

This releases the stack space allocated by the stack frame.

The leaveq instruction then pops the value pointed to by %rsp into %rbp and thus restoring the calling procedure’s stack frame

Note that the leaveq instruction is functionally equivalent to the instructions mov %rsp, %rbp and pop %ebp.

The leaveq is then followed by a retq instruction.

At the point that the retq instruction is being executed, the stack pointer %rsp points to the address 4 bytes above the saved value of %rbp, which is the return address of the next instruction in the callee function’s code to be executed.

The retq instruction pops the return address from the stack into the instruction pointer %rip, which points to the next instruction to be executed.

Thus the program will resume executing at the saved return address (which was pushed onto the stack by the caller function).

Note that the NOPW is a no-op instruction, which stands for no operation.

The instruction does nothing but simply takes up a word sized byte for alignment purposes so that a code sequence ends on a particular memory boundary.

Assembler and Linker

To turn the assembly code into machine code, there is an assembler that generates a binary object file. Then, a static linker looks at the main binary and resolves any imports that the main binary might need, creating another binary object file that includes all the required static libraries. Note that there is also dynamic linking, which is when shared libraries are imported at run time. Also note that when people say compile they generally mean the entire process: preprocessing, compiling, assembling, and linking.

Dynamic Linking vs Static Linking Aside

In static linking, the entire library of a function that the main program is using is copied over and compiled, which may result in a lot of unnecessary bloat. Dynamic linking solves this problem by linking the libraries that the main program requires at run time. The downside is that while compilation time and resulting binary size is decreased, running time is increased because of the need to import functions being used during runtime.

In our code, we have #include <stdio.h>.

This line uses the #include preprocessor to tell the compiler what libraries to import.

On Linux, C standard libraries like stdio are by default linked dynamically.

Static Library vs Shared Library Aside

When program is linked against a static library, machine code from the object files for any external functions used by the program is copied from the library into the final executable.

A shared library is handled with dynamic linking, which makes the executable file smaller than if the library were static. Dynamic linking works by including only the functions that the main executable requires (instead of the complete machine code from the object files for the external functions that a static library would include). Before the executable file starts running, the machine code for the external functions is copied into memory from the shared library file on disk by the OS. The advantage is that the library can be updated without recompiling the programs which use it. With dynamic linking of shared libraries, one copy of a library can be shared between multiple programs.

Executable Format

Note that this blog post specifically covers compilation on x86 processors, specifically x86-64 (the 64 bit version). The term x86 refers to a family of instruction set architectures. An instruction set architecture can be thought of as an abstract model of a computer. It specifies the architecture and the programming environment that processors supporting x86 must support, including the instruction set supported, the types of registers, and the data types. A CPU is an example of an implementation of an instruction set architecture.

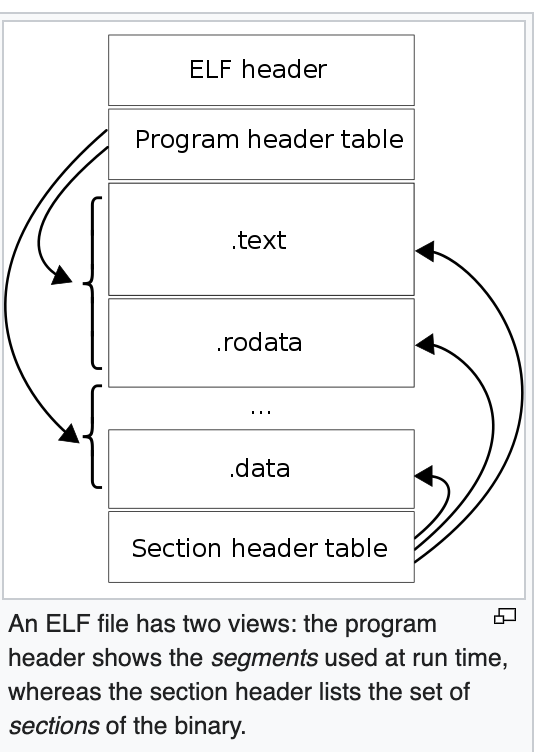

On x86 processors, the ELF format (Executable and Linkable Format) is the standard binary file format. This ELF file is the output of the assembler as described in the process above.

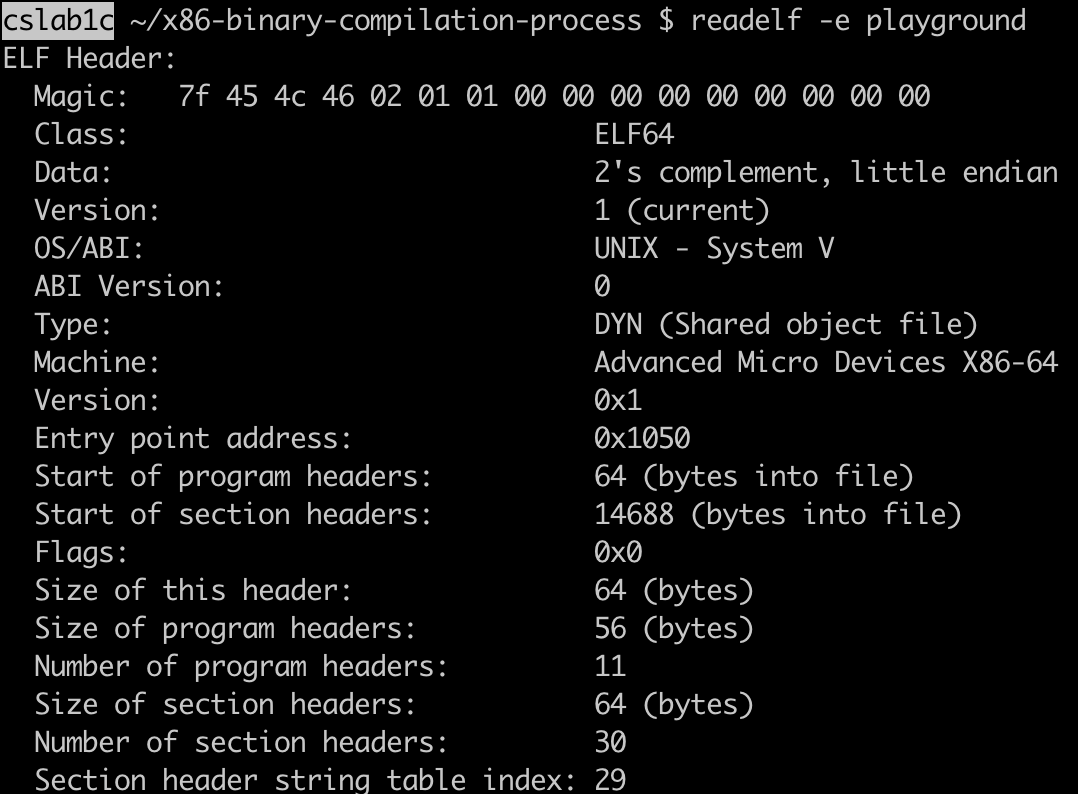

We can view our program’s elf binary after the entire compilation process using readelf -e playground.

ELF Header

ELF files have three parts: the elf header, section headers, and program headers. The elf header general information about the binary, such as the byte ordering (i.e. endianness), whether to use 32-bit or 64-bit addresses, and the type of the ELF binary.

There are multiple types of ELF binaries: REL (relocatable object file), DYN (representing a shared library), and EXEC (the final product). Note that the output of the assembler before linking is a binary of type REL. This is because at that stage, the code in the binary does not contain exact addresses. After the linker, we should get an EXEC. However, we are getting a ELF of type DYN. This is because GCC, our compiler, by default enables PIE (position independent code). This means that the addresses are not finalized yet. The purpose of PIE is to achieve ASLR (address space layout randomization) to make it harder for bad actors to hijack the binary by knowing the exact locations of parts of the binary during runtime.

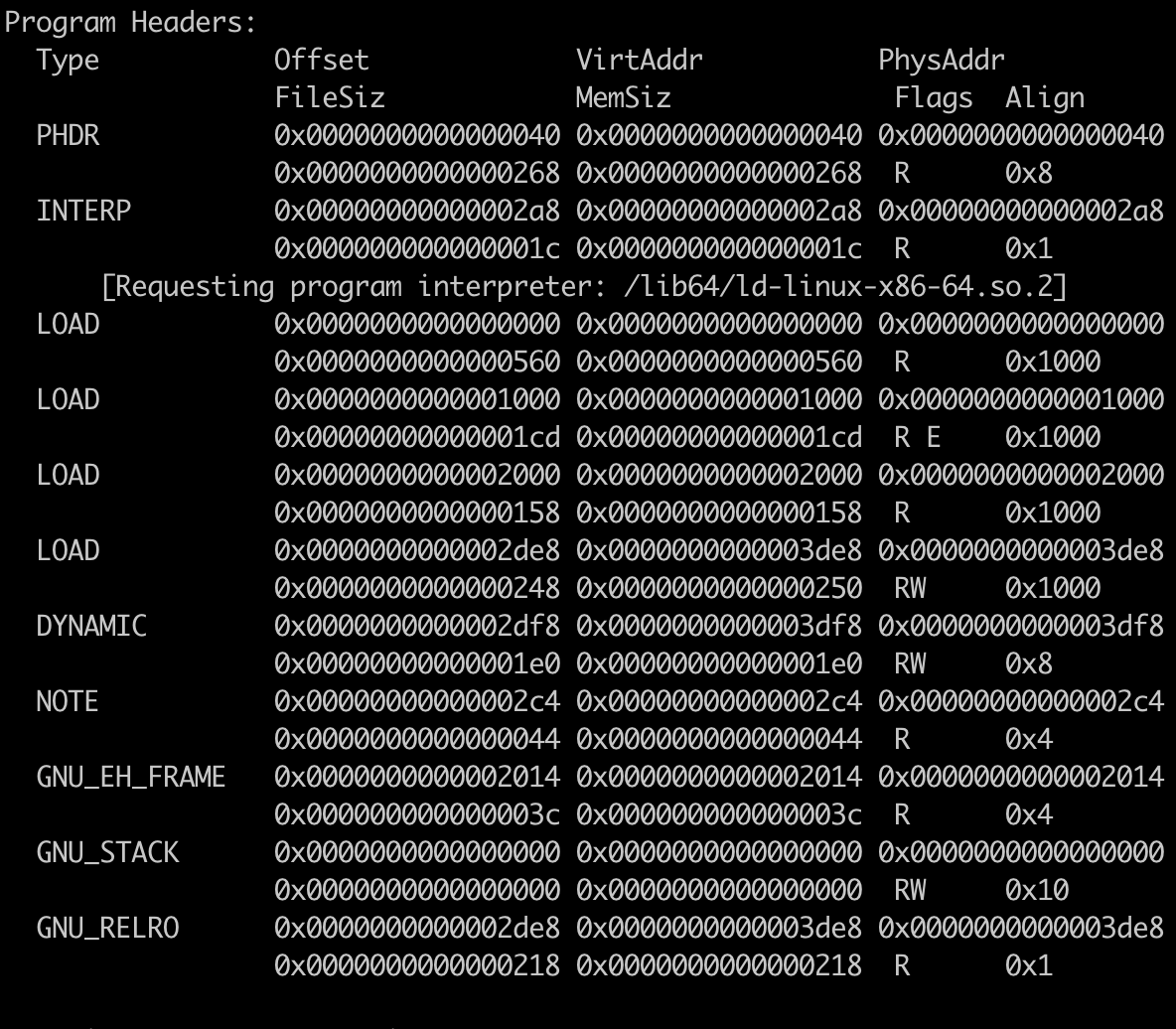

Program Headers

The purpose of the program header is to tell the OS how to load the program binary into memory and execute it.

Note that the program header is requesting a program interpreter.

Even though C is a compiled language, the compiler uses this interpreter during dynamic loading, which involve the final steps needed to complete the loading and prepare the program for execution.

The purpose of the program header is to tell the OS how to load the program binary into memory and execute it.

Note that the program header is requesting a program interpreter.

Even though C is a compiled language, the compiler uses this interpreter during dynamic loading, which involve the final steps needed to complete the loading and prepare the program for execution.

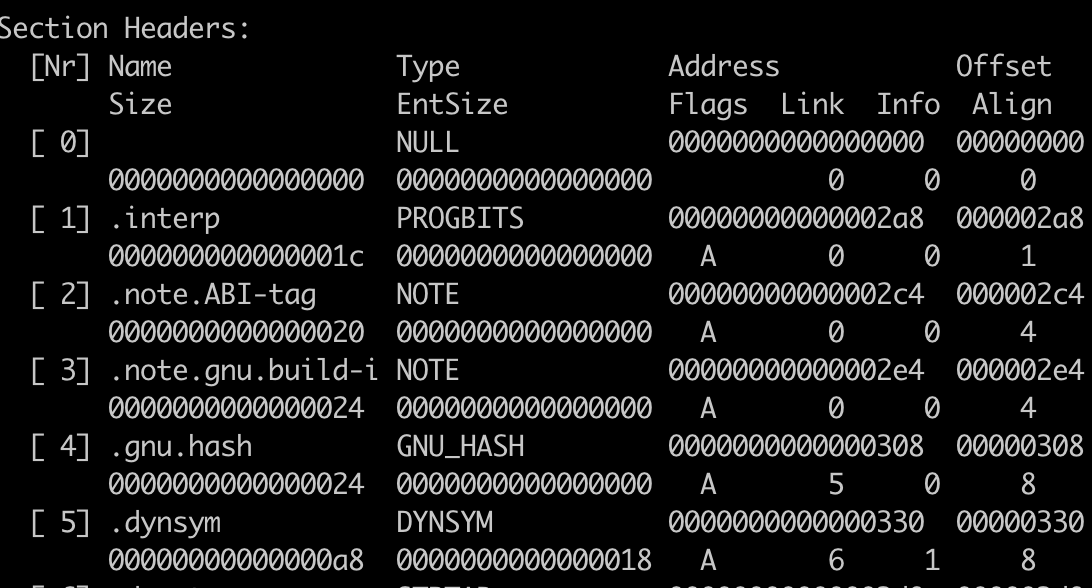

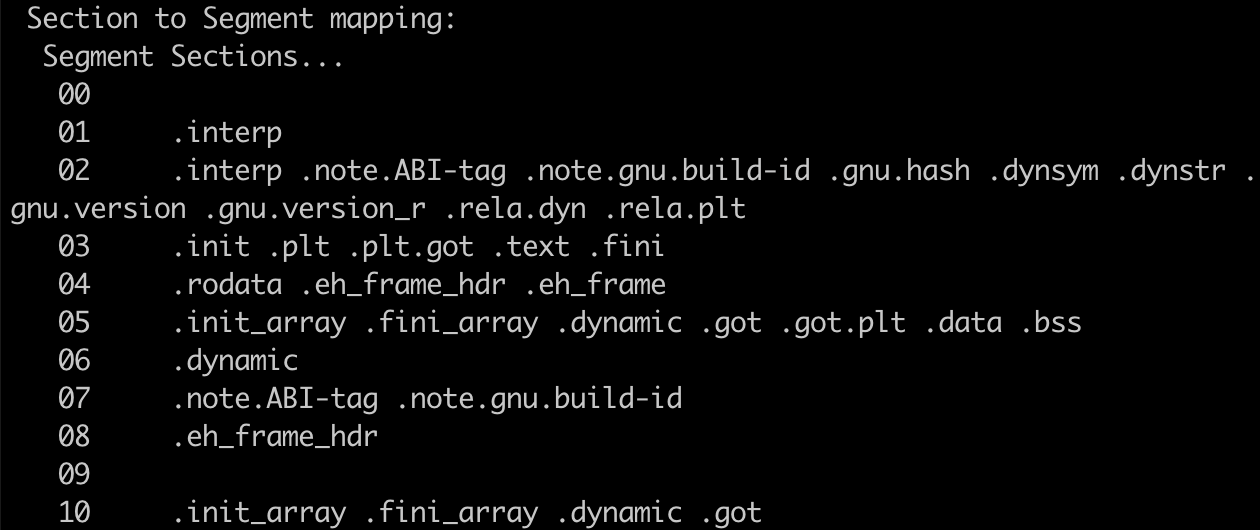

Section Headers

Sections make up segments, which are part of the program header. Note that only the first few sections are included in the picture for brevity.

We can see that there is a Section to Segment mapping section where sections are assigned to segments.

The section header contains meta data about the sections, including the location, the size and the name.

The sections are used to divide up the binary logically as described in more detail in the next section Running the program.

The .text section contains the executable code.

The .data section holds initialized data.

The .bss section holds uninitialized data.

Program Execution

When we run the program, a process is created and the program represented by an ELF is loaded from the file into the process’s address space.

The executable file has instructions for the OS on the address space layout.

The OS looks at the ELF to load segments into memory and for invoking a user space run-time linker program.

The process’s single thread of control then executes the program’s code.

This program consists of executable code and data.

Note that the code, once loaded, is never modified.

On the other hand, much of data is modified so it makes sense to divide the two and put the code in a part of the address space that prevents modification.

We could put all data in a readable writable region but that’s not necessarily what we want.

There are global and local variables.

Global variable’s scope is the entire program.

Local variables scope is just the block and are not needed after the thread exits the local variable’s scope.

Therefore, we will have different sections for each.

These sections are described previously in the Section Headers part.

The OS also allocates the stack and the heap for the program. The stack is used for local variables of fixed size. We encountered this previously in the Calling Conventions Aside when analyzing the assembly code. The heap is used for dynamic memory location and variables allocated here can be accessed globally.

Resources

- Code used in blog post

- 32 Bit x86 Calling Conventions

- Stack vs Heap

- Textbook: Operating Systems in Depth

- Compiling, Linking, and Building C/C++ Applications

- How Programs Get Run: ELF Binaries

- ELF Structure