Operating Systems in a Nutshell

This blog post introduces Operating Systems and the pieces involved, specifically: processes and threads, drivers, file systems, and virtual memory.

Post Outline

Intro

In a previous blog post C Source Code to x86 Binary, we detailed how C source code is compiled into x86 binary. We ended with a brief section that described at a high level how an OS runs the compiled user binary. This blog post aims to go into more detail.

At a high level, what does an OS need?

Processes and Threads

One obvious answer are processes and threads. Processes represent programs that are being executed. A process can have multiple threads of execution. It’s important to note that in an OS, there are two levels of permissions: kernel mode and user mode.

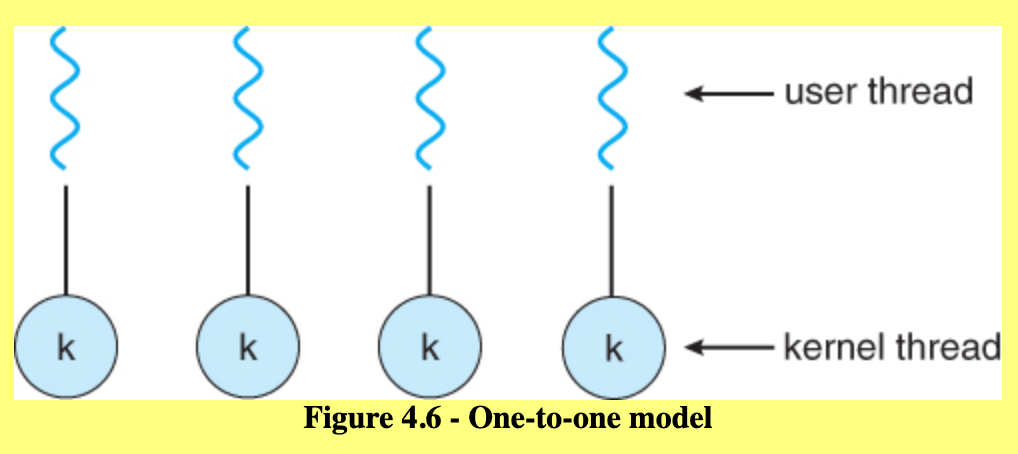

There are several different ways to have multithreading in an application and they stem from having these two different modes. There are user threads and kernel threads. User threads are added and used by application programmers. Kernel threads are implemented and used by the OS kernel. User threads are mapped to kernel threads in a way that depends on the OS’s implementation. For example, we could have a many to one model in which many user level threads are mapped to a single kernel thread. We could have a one to one model in which each user thread is mapped to its own kernel thread. We could also have a many to many model in which many user threads are multiplexed on many kernel threads.

Note that true parallelism can only truly be achieved if the chip of the computer has multiple cores (i.e. multiple CPUs on a single chip). Also note that the POSIX standard defines the specification for pthreads, not the implementation.

Drivers

An OS will need a way to interact with hardware, such as keyboards, mice, and disks. The software that handles these interactions are called drivers. For example, in order for a user to interact with a terminal via a keyboard, an OS might have a buffer that reads in what users type. When an enter (i.e. new line character is pressed), the OS would read in what is in the buffer up until the new line and attempt to interpret it as a command.

File System

An operating system will also typically have a file system. A file system’s purpose is to provide permanent storage to the OS. An OS’s file system differs from database systems in that data systems are built to handle large amounts of data. An OS’s file system, on the other hand, is used to hold programs, source code, and local directories and files. OS’s will usually have a virtual file system, which can be thought of as an interface that actual file system’s must implement. For example, a virtual file system will define signatures of functions such as open, close, read, and write. An actual file system will provide the implementation details for those functions.

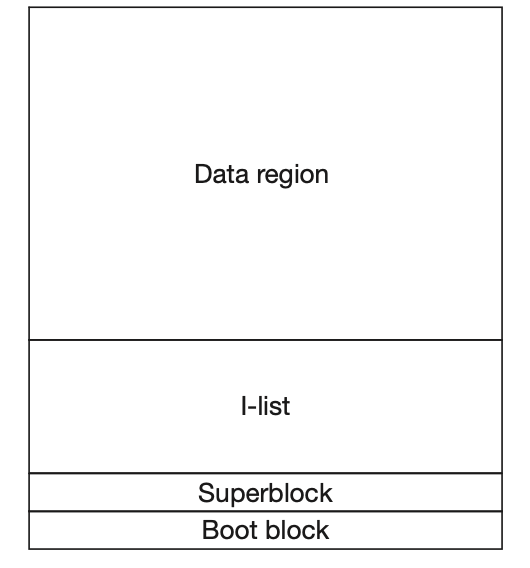

The actual file system will typically be on disk, meaning that data can be stored in non volatile memory that will still exist after the OS turns off or crashes. The disk representation of a file system is important in the performance of file systems. In S5FS, a very early Unix file system, there are four key components:

- the boot block

- the super block

- the inode list

- the data region

Together, these components form the file format on disk of the file system. The boot block connects the operating system and the file system; it contains the initial program stored on the disk that begins the loading of the operating system. The super block describes the layout of the rest of the disk. It contains metadata such as the start of the free list. The inode list contains an array of nodes that can be used to represent a file. The data region contains the data corresponding to the files included in the inode list.

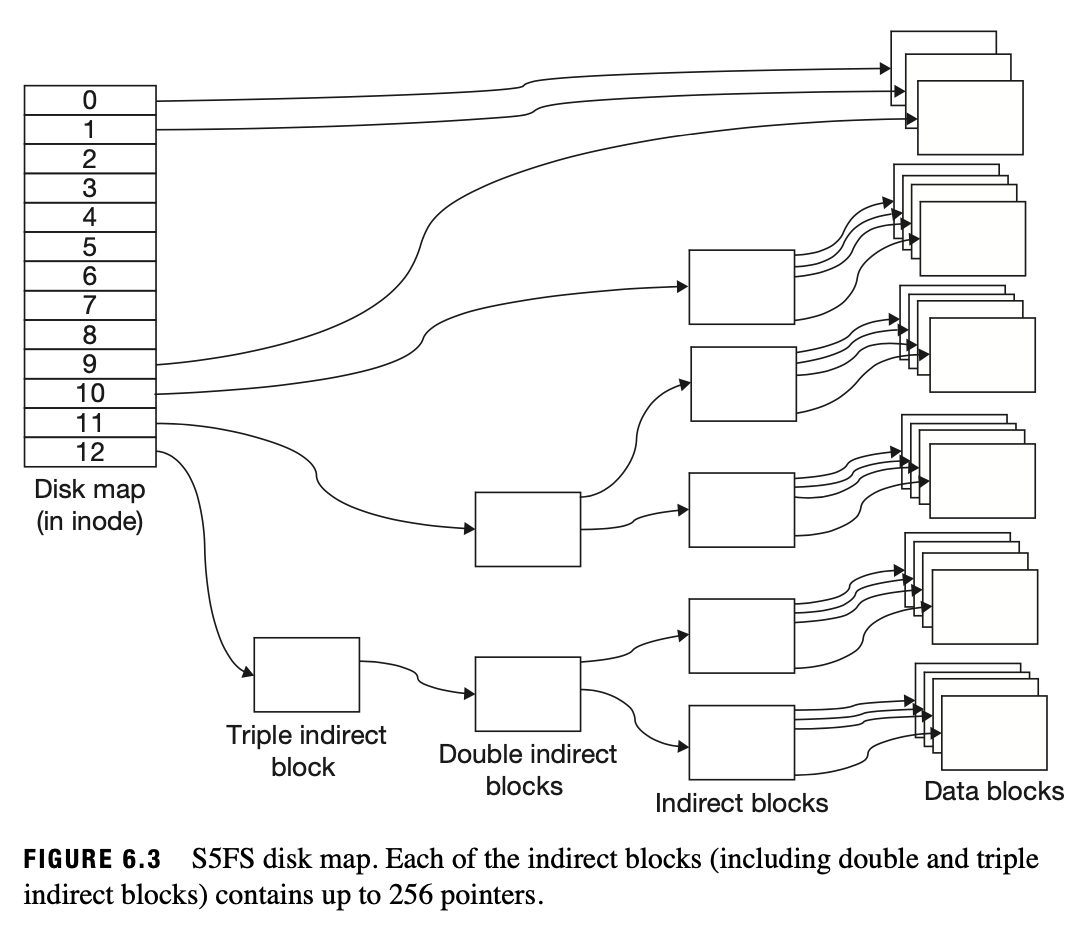

One interesting part of the design of the data region in S5fs in the concept of direct and indirect blocks. There are a certain number of direct blocks that directly contain a file’s contents. Then there are some indirect blocks which are pointers to blocks that point to blocks. There can be multiple levels of indirection with an indirect block pointing to another indirect block that points to actual file blocks. With this design, sequentially accessing a file is efficient. In addition, representing sparse files where huge chunks of the file are empty is very efficient. This is because we can have indirect blocks point to nothing, indicating no data is stored there. A downside is that accessing actual data in the indirect blocks is slower as multiple layers of indirect blocks have to be traversed.

Virtual Memory

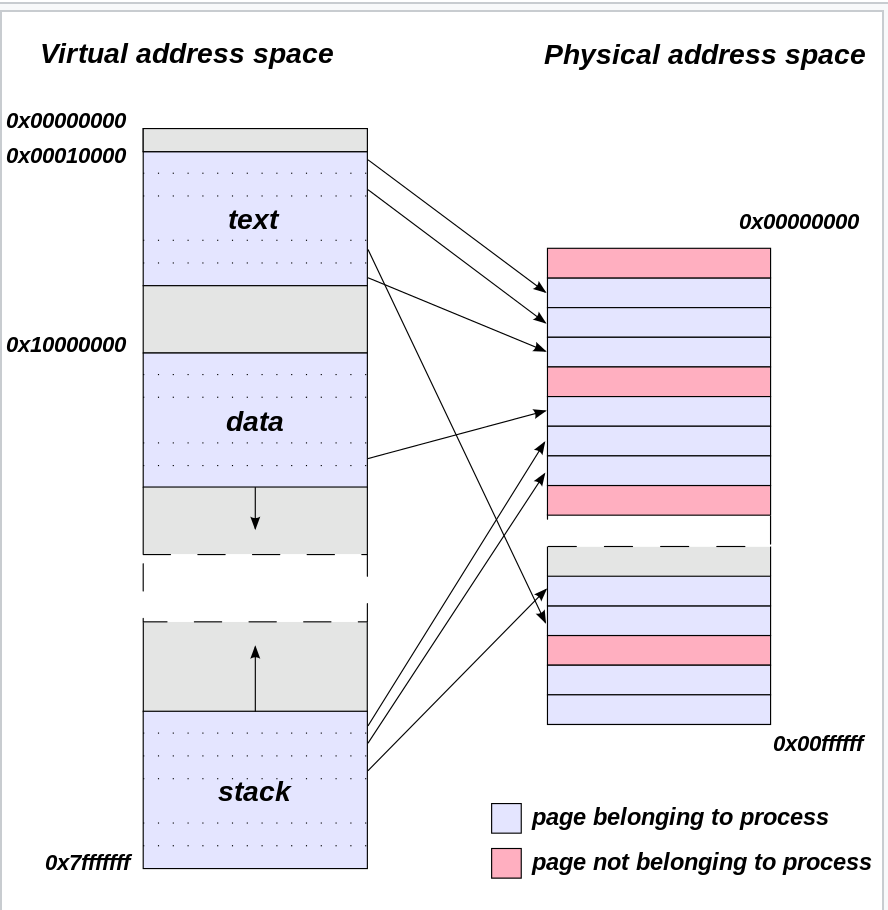

One of the key components of an operating system is virtual memory. Virtual memory is a technique in representing memory in an idealized perspective separate from what actual physical memory may be structured. In the idealized perspective, each process has its own virtual view of memory that is isolated from the virtual memory of other processes.

Because the memory is virtual, the memory of all the processes don’t have to actually be in main memory all the time. They can be mapped in from disk as needed, which is significantly cheaper.

The pages that are being mapped to and from disk and memory correspond to the different parts of a process’s virtual address space such as the text (containing the source code), the data, the stack (stores local variables/function calls), the heap (dynamic memory allocation), and more.

The sections are also covered in this blog post.

These different areas can be stored as a linked list where each allocated piece of memory represents a part of the process’s virtual address space. This is typically called a virtual memory map.

Note that not all of these different parts need to be backed to disk. For example, the stack and the heap are only relevant to the process when it’s running.

In an OS, there is a system process called fork which creates an exact copy of the parent process called the child process. This can be very slow if we were to actually copy over each page. Instead, we can lazily copy over areas and only create a new modification if a process actually modifies the area (performing a write). We can use shadow objects, which can be thought of as a tree representation where the root is the original object. Everytime a modification is made by a forked process, a new child shadow object is spawned that holds the modifications from the parent shadow object above it. This technique of only creating a new object upon modification is called copy on write.

So we now know what we’re mapping, but how does the actual mapping work? Whenever we encounter a page fault in user space, we use a page fault handler which is a function that takes in a virtual user address that isn’t mapped into memory yet, finds the page on disk containing the user address and maps it in. The main part of this mapping process uses a cache called a Translation Lookaside buffer (TLB). The TLB cache holds physical addresses that were previously read in and stored. If the corresponding physical address is not found, then we have to go back to disk to find the physical address.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we covered the core parts that make up an OS, from the processes and threads that run programs to the drivers that allow users to interact with the computer physically to disks that allow data to be stored, to virtual memory which allows for an efficient and effective method of mapping between data on disk and memory processes.